Now that I’ve written the dovetail post, it has occurred to me that I may have jumped the gun a little bit. The dovetail is an incredible, beautiful joint, but it’s just one of many. So for this post, I’m going to zoom out and break down the basics of traditional joinery. After all, joinery does define a timber frame.

A joint is the area where two separate pieces connect. In timber framing, there are many different types of joints and connections. A frame can be completely constructed using traditional joinery, or a frame can be constructed using joints that are reinforced with steel plates and steel ties that are capable of carrying particularly heavy structural loads. Let’s start with traditional joinery.

The traditional way to join one timber to another is by making cuts in the wood so the two beams can fit together like puzzle pieces. Female and male cuts are made in the timber. The male cuts of timber are inserted into the female cuts to create a connection. The connection is held secure with hardwood pegs that are hammered into the joint.

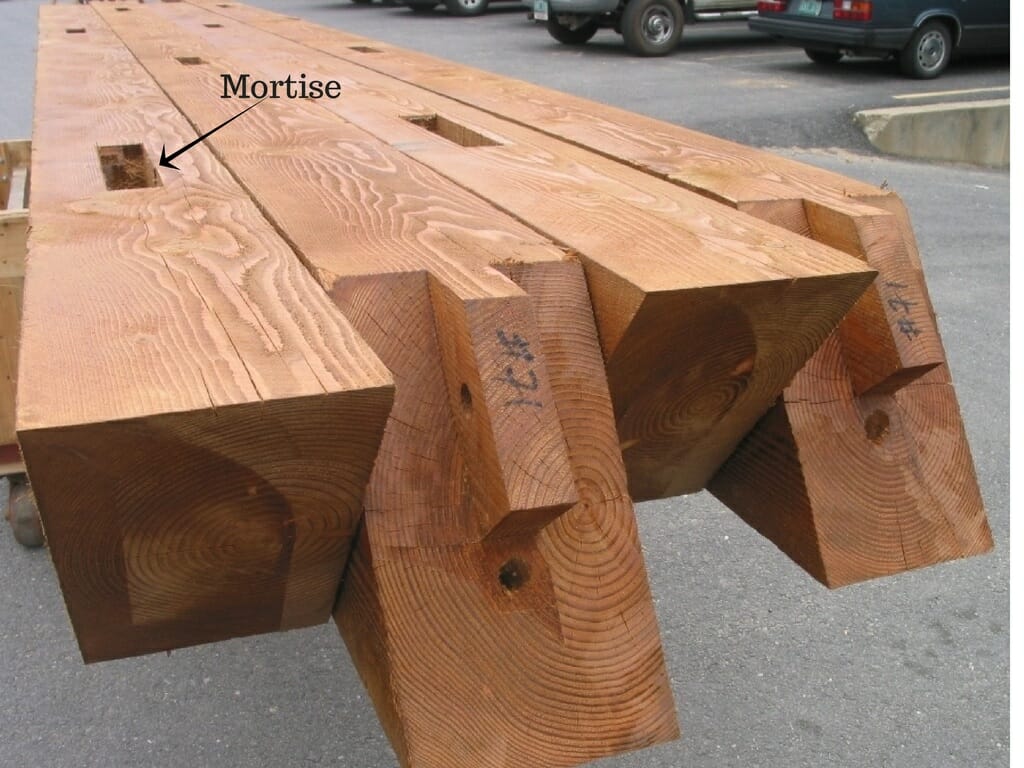

A Mortise is the female part of a joint. It is a notch, hole, or cut in a piece of wood into which a Tenon is inserted.

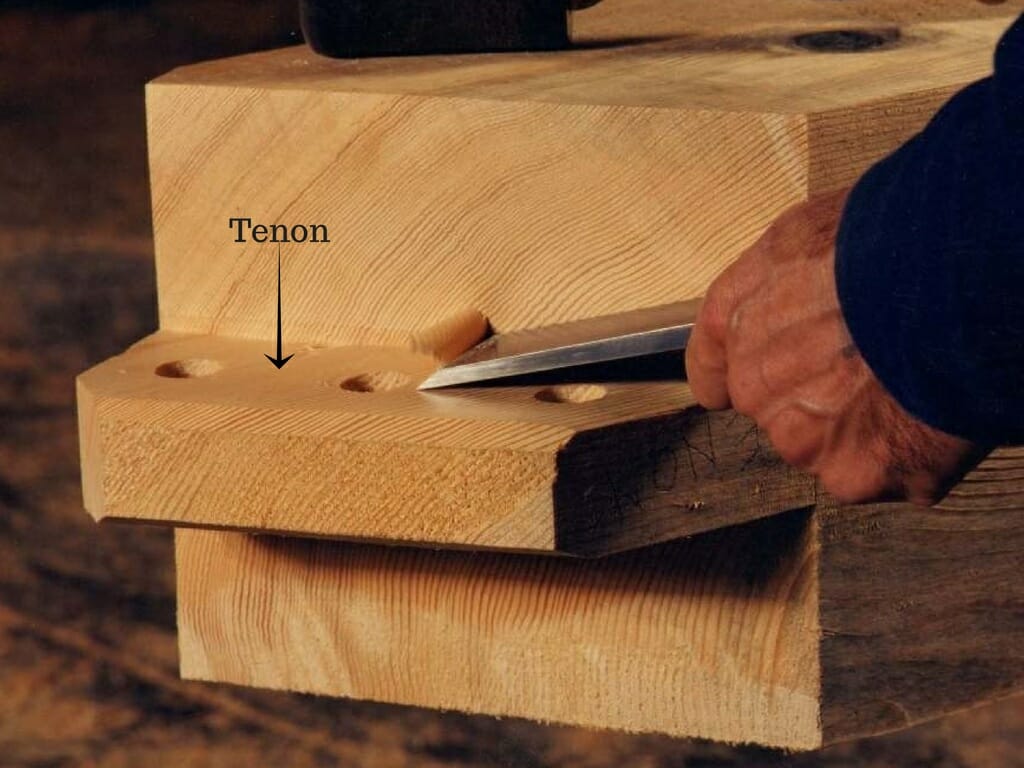

A Tenon is the male part of a joint. It is the cut end of a timber that fits into a mortise.

Hardwood pegs are used to further fasten mortise and tenon connections.

Timbers that are connected using mortise and tenon cuts with hardwood pegs are traditionally joined. The geometry of the joints carries structural loads and the hardwood pegs hold the joints secure. Traditional framing requires no nails, steel, or any metals. The way the wood is connected creates a secure, strong frame that can stand for hundreds of years.

At Vermont Timber Works, pride is taken in all parts of the timber framing process. There are experts in the shop, and in the office, who have been in the framing business for over 20 years, so they know a thing or two about crafting strong and beautiful timber connections.

Thanks for stopping by our timber framer’s blog! If you like this post, or have any timber work questions, we encourage you to get in contact, ask as expert, or share your thoughts in the comment section below!

Very nice overview. The photos are beautiful, too, so that always helps.

Excellent.

It would be great to extend the discussion to hinged (Pinned) connection and moment resisting connection too.

Hi,

We are considering purchasing a timber frame resale home in NC. We noticed some of the wooden pegs extend further out of the timbers than others. They are not uniform. Does that matter in regard to the structural integrity of the home?

Thanks,

Stefanie

This is an old thread, but the answer may help others! The pegs are typically made of white oak, for the wood’s natural resistance to water, straight grain, and shear strength. Traditionally, the pegs are soaked in linseed oil to lubricate them for ease of driving through the joint, and when dry, prevents slippage, though pegs generally are locked quite tightly due to shear moment of the timbers. It is common for builders to simply drive them until they will not penetrate further, which can vary depending on wood density, knots, etc. Purists often leave them however they ended up, while others variously cut them flush, cut and dress to button ends, or cut to uniform lengths. How much they are cut can also be based on where they are located. In a coatroom, kitchen, or den, they make handy and decorative hangers. But, in a passage way, low ones can be nuisances or hazards.